Rita Gerlach lives with her husband and two sons in a historical town nestled along the Catoctin Mountains, amid Civil War battlefields and Revolutionary War outposts in central Maryland. Her fourth book,

Surrender the Wind, an inspirational historical romance set in Virginia and England, released from Abingdon Press in August 2009. She is currently working on her

Daughters of the Potomac Series which will release in 2012.

"This novel set after the American Revolution has something for everyone: romance, mystery, comedy and intrigue. The descriptions of the estate, church grounds and characters, especially Seth and Juleah, help bring this novel to life. The writing is so vivid you'll even be able to hear the horses' hoofs and people's voices." -- Romantic Times Magazine

Surrender the Wind is the story of Seth Braxton, a patriot of the American Revolution, who unexpectedly inherits his loyalist grandfather’s estate in England. Seth is torn between the land he fought for and the prospect of reuniting with his sister Caroline, who was a motherless child taken to England at the onset of the war.

With no intention of staying permanently, Seth arrives to find his sister grieving over the death of her young son. In the midst of such tragedy, Seth meets Juleah, the daughter of an eccentric landed gentleman. Her independent spirit and gentle soul steal Seth’s heart. After a brief courtship, they marry and she takes her place as the lady of Ten Width Manor, enraging the man who once sought her hand and schemed to make Ten Width his own.

From the Virginia wilderness to the dark halls of an isolated English estate, Seth and his beloved Juleah inherit more than an ancestral home. They uncover a sinister plot that leads to murder, abduction, and betrayal--an ominous threat to their new life, love, and faith.

Surrender the Wind

The Wilds of Virginia

October, 1781

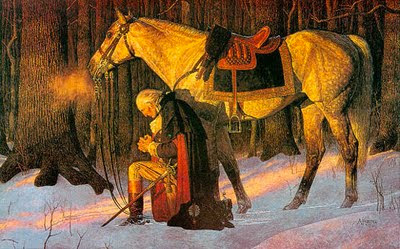

On a cool autumn twilight, Seth Braxton rode his horse through a grove of dark-green hemlocks in a primeval Virginia forest, distressed that he might not make it to Yorktown in time. He ran his hand down his horse’s broad neck to calm him, slid from the saddle, and led his mount under the deep umbra of an enormous evergreen. Golden-brown pine needles shimmered in the feeble light and fell. In response to his master’s touch, the horse lifted its head, shook a dusty mane, and snorted.

“Steady, Saber. I’ll be back to get you.” Seth spoke softly and stroked the velvet muzzle. “Soon, you’ll have plenty of oats to eat and green meadows to run in.”

He threw a cautious glance at the hillside ahead of him, drew his musket from a leather holster attached to the saddle, and pulled the strap over his left shoulder. Out of the shadows and into bars of sunlight, he stepped away to join his troop of ragtag patriots. Through the dense woodland, they climbed the hill to the summit.

Sweat broke over Seth’s face and trickled down his neck and into his coarse linen hunting shirt. He wiped his slick palms along the sides of his dusty buckskin breeches and pulled his slouched hat closer to his eyes to block the glare of sun that peeked through the trees. A lock of dark hair, which had a hint of bronze within its blackness, fell over his brow, and he flicked it back with a jerk of his head. Tense, he flexed his hand, closed it tight around the barrel of his musket, and listened for the slightest noise—the soft creak of a saddle or the neigh of a horse. His keen blue eyes scanned the breaks in the trees, and his strong jaw tightened.

Shadows quivered along the ground, lengthened against tree trunks, then crept over ancient rocks. Within the forest, blue jays squawked. Splashes of blood-red uniforms interspersed amid muted green grew out of earthy hues.

A column of British infantry, led by an officer on horseback, moved around the bend. His scarlet coat, decked with ivory lapels and silver buttons, gleamed in the sunlight, his powdered wig snow white. An entourage of other lower-ranking officers accompanied him alongside the rank and file.

Without hesitation, Seth cocked the hammer of his musket to the second notch and pressed the stock into his shoulder. “Wait.” Daniel Whitmann, a young Presbyterian minister, pulled out his handkerchief, mopped the sweat off his face, and shoved the rag back into his pocket. “Wait until more are on the road. Wait for the signal to fire.”

Seth acknowledged the preacher with a glance. “Pray for us, Reverend, and for them as well. Some of us are about to face our Maker.”

Whitmann moved his weapon forward. “God shall not leave us, Seth. May the Almighty’s will be done this day.”

Seth fixed his eye on the target that moved below. He aimed his long barrel at the heart of the first redcoat in line. No fervor for battle rose within him, only a heartsick repulsion that he would take a boy’s life, a lad who should be at home tending his father’s business or at school with his mind in books. The boy lifted a weary hand and rubbed his eyes. The officer nudged his horse back and rode alongside the boy. “Stay alert, there!” The boy flinched, stiffened, and riveted his eyes ahead.

A muscle in Seth’s face twitched. He did not like the way the officer cruelly ordered the boy. With a steady arm, he narrowed one eye and made his mark with the other. He moved his tongue over his lower lip and tried to control a heated rush of nerves. He glanced to the right, his breath held tight in his chest, and waited for the signal to fire. His captain raised his hand, hesitated, then let it fall.

Flints snapped. Ochre flashed. Hissing reports sliced the air. The British surged to the roadside in disorder. Their leader threatened and harangued his men with drawn sword. He ordered them to advance, kicked laggards, and shoved his horse against his men, while bullets pelted from the patriots’ muskets.

Seth squeezed the trigger. His musket ball struck the officer’s chest. Blood gushed over the white waistcoat and spurted from the corner of the Englishman’s mouth. He slid down in the saddle and tumbled off his horse, dead.

“Fall back!” Redcoats scattered at the order, surged to the roadside, slammed backward by the force of the attack. The fallen, but not yet dead, squirmed in the dust and cried out. A redcoat climbed the embankment, slipped, and hauled back up. His bayonet caught the sunlight and Seth’s attention. The soldier headed straight for Whitmann.

His hands fumbled with his musket, and Whitmann managed to fire. The musket ball struck the redcoat through the chest. A dazed look flooded the preacher’s face.

Seth grabbed Whitmann by the shoulder and jerked him away. “Don’t think on it, Reverend.”

He shoved the heartsick minister behind him. A troop of grenadiers hurried around the bend in the road, their bayonets rigid on the tips of their long rifles. They faced about, poured a volley into the hilltop, and killed several patriots.

A musket ball whizzed past Seth’s head and smacked into the tree behind him. Bark splintered, and countless wooden needles launched into the air. His breath caught in his throat, and he pitched backward. Blood trickled from his temple, hot against his skin. He rolled onto his side, scrambled to a crouched position, and slipped behind a tree. Beside him, Whitmann lay dead, his bloody hand pressed against the wound, the other clutched around the shaft of his rifle, with his eyes opened toward heaven.

“Retreat! Retreat!” The command from a patriot leader reached Seth above the clamor of musket fire. With the other colonials, he ran into the woods. His heart pounded against his ribs. His breathing was hurried.

He glanced back over his shoulder and saw that he must run for his life. Redcoats stampeded after him through the misty Virginia wilds. His fellow patriots scurried up the hill ahead of him and slipped over the peak. With unaffected energy, he mounted the slope to follow them and ran as fast as his legs could carry him over the sleek covering of dead leaves. He had to catch up. Exhausted, he forced his body to move, crested the hill, and hastened over it, down into the holler of evergreens.

Without a moment to lose, Seth leapt into the saddle of his horse, dug in his heels, and urged Saber forward. The crack of a pistol echoed, and a redcoat’s bullet struck. Against the pull of the reins, the terrified horse twisted and fell sideways. Flung from the saddle, Seth hit the ground hard, and his breath was knocked from his body. For a tense moment, he struggled to fill his lungs and crawl back to his fallen horse. His heart sank when he saw the mortal wound that had ripped into Saber’s hide. Desperate for revenge, Seth grabbed his weapon and scrambled to his feet. But the click of a flintlock’s hammer stopped him short.

“Drop your weapon, rebel.” A redcoat stood a stone’s throw away, his long rifle poised against his shoulder.

Seth opened his hand and let his musket fall into the leaves. Soldiers hurried forward and confiscated his knife and musket, shot and powder horn. Saber moaned, and from the corner of Seth’s eye, he saw his faithful mount struggle to rise.

The redcoat that held him at gunpoint glanced at the suffering horse, and a cruel light spread across his face. Helpless, Seth watched the redcoat take the musket from a soldier and aim. The forest grew silent, and Seth’s quickened heartbeat pulsed in his jugular. He clenched his teeth and shut his eyes. Then his musket ended his horse’s misery.

At the blast, Seth jerked. He stepped back from the putrid smell of rum and sweat, from the pocked face that glistened with grime, and from the eyes that blazed with sordid pleasure. A firm voice gave orders to make way as an officer on horseback cantered toward him. The Englishman dismounted, took Seth’s musket from the rum-smelling buffoon, and turned it within his hands.

“Iron. Smoothbore barrel. Maker’s mark.” The officer examined the craftsmanship of the wood and forged brass. “Walnut full stock. Board of Ordnance Crown acceptance mark on the tang. Regulation Longland, I’d say. A quality piece by American standards.”

Seth bit his lower lip and clenched his fists. “I cannot kill any of your men. It’s not loaded. You have my shot and powder. Return them to me.”

The officer handed the musket over to an Iroquois scout. “A gift. Show it to your people. Tell them the king of England wished you to have it.”

“We captured a rebel.” The redcoat who shot Seth’s horse threw his shoulders back.

Colonel Robert Hawkings stood nose-to-nose with the soldier. “You think yourself worthy of some reward? One prisoner is something to boast about?”

Corporal John Perkins nodded. “Better than none at all, sir.”

“Out of my sight, you foul-smelling oaf.”

Perkins shrank back, red-faced. Hawkings planted himself in front of Seth and met his eyes. “Your colonials killed several of my men, including our major. Not only are you a rebel, but a murderer as well. You’ll hang for it.”

Seth stared straight into his enemy’s eyes. “It would be better to suffer the noose than be under the bootheels of tyrants.”

Blue veins on Hawkings’s neck swelled and he struck Seth across the face. Seth’s head jerked from the force of the blow. Slowly, he turned back and spat out the blood that flooded his mouth.

Nearby a younger officer watched. His expression burned with arrogant pride. Seth noticed the tear in the man’s jacket and saw a stream of blood had stained the white linen beneath it.

To the rear, another man stepped forward.

“Colonel Hawkings, trade this prisoner for one of our own.” He spoke in a quiet, controlled tone.

Hawkings’s brows arched, and he spun halfway on his heels. “Captain Bray, you have no satisfaction in seeing a traitor hang?”

“Hanging is for those who have been tried and sentenced. This man has not had that afforded him.”

“He deserves nothing in that regard.”

“Our government has given prisoners of war the rights of belligerents, sir. They’re not to be executed.”

“You doubt my authority in this matter?” Hawkings said.

Bray’s frown deepened. “No, sir, only your better judg-ment.”

“Stand back. I’ll shoot this rebel myself.”

Hawkings drew his pistol, pointed it at Seth’s head and cocked the hammer. Stunned, Seth’s breath caught in his throat. His body stiffened in a cold sweat.

Bray lunged and cuffed Hawkings’s wrist. “He’s unarmed.”

Hawkings shoved Bray back. “Take your hands off me. You dare defy me?”

“We are Englishmen and Christians. Let us abide by the rules of just conduct.”

Hawkings grabbed Bray’s coat and yanked his face close. “I am the officer in charge. I can do anything I wish.”

“Shooting an unarmed man is murder,” Bray said.

Hawkings paused. His expression grew grave as though he considered the word murder with great care. A moment later, he lowered his pistol. “Murder, you say? Well, I’ve had enough blood this day. I know my officers shall agree this man is guilty and that hanging is a more just and merciful punishment. Perkins, secure this rebel under that tree, the one I mean for him to swing from at dawn. Let him listen to its branches creak all night. Perhaps that will humble his rebellious heart.”

Hawkings strode off. Perkins grabbed hold of Seth and tied his wrists together. Seth lowered his eyes, stared at the ground, and refused to give Bray any sign he was grateful he had stood up for him.

“If I were you, I’d mind my place, Bray.”

Seth lifted his eyes to see Bray turn to the man who taunted him.

“Have you no honor, Captain Darden?” Bray said. “A man must speak up for justice.”

Darden pulled away from the tree he leaned against. “If you do not take care to show respect to Colonel Hawkings, you’ll regret your interference. You should know what meddling could do, after what happened at Ten Width.”

Seth let out a breath and frowned. What did these men know of Ten Width, his grandfather’s estate in England? Yanked forward, he caught Darden’s stare. Within the depths of his palegray eyes burned hatred. A corner of Darden’s mouth curled and twitched. To stay silent, Seth bit down hard on the tip of his tongue.

They led him to the oak, where he struggled with the understanding he’d die young at twenty-six. Under the shadow of the tree’s colossal branches, he cried inwardly, Let the sighing of the prisoner come before thee; according to the greatness of thy power preserve thou those that are appointed to die.

Seth’s burdened heart hoped heaven heard him, but his weakened flesh doubted.

GIVEAWAY: Copy of Surrender the Wind. Leave your comment and email address. ACFW Book Club members - this is your September book of the month for historical fiction.